Qualitative Analysis

Sources:

CONTRUCTING GROUNDED THEORY (CHARMAZ) SOCIAL RESEARCH METHODS (BRYMAN) BASICS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH (CORBIN, STRAUSS)

About Analysis

Usually depends on unstructured textual material (prose), which isn’t trivial to analyze.

3 general approaches to analysis:

- analytical induction

- Grounded Theory

- Narrative Analysis

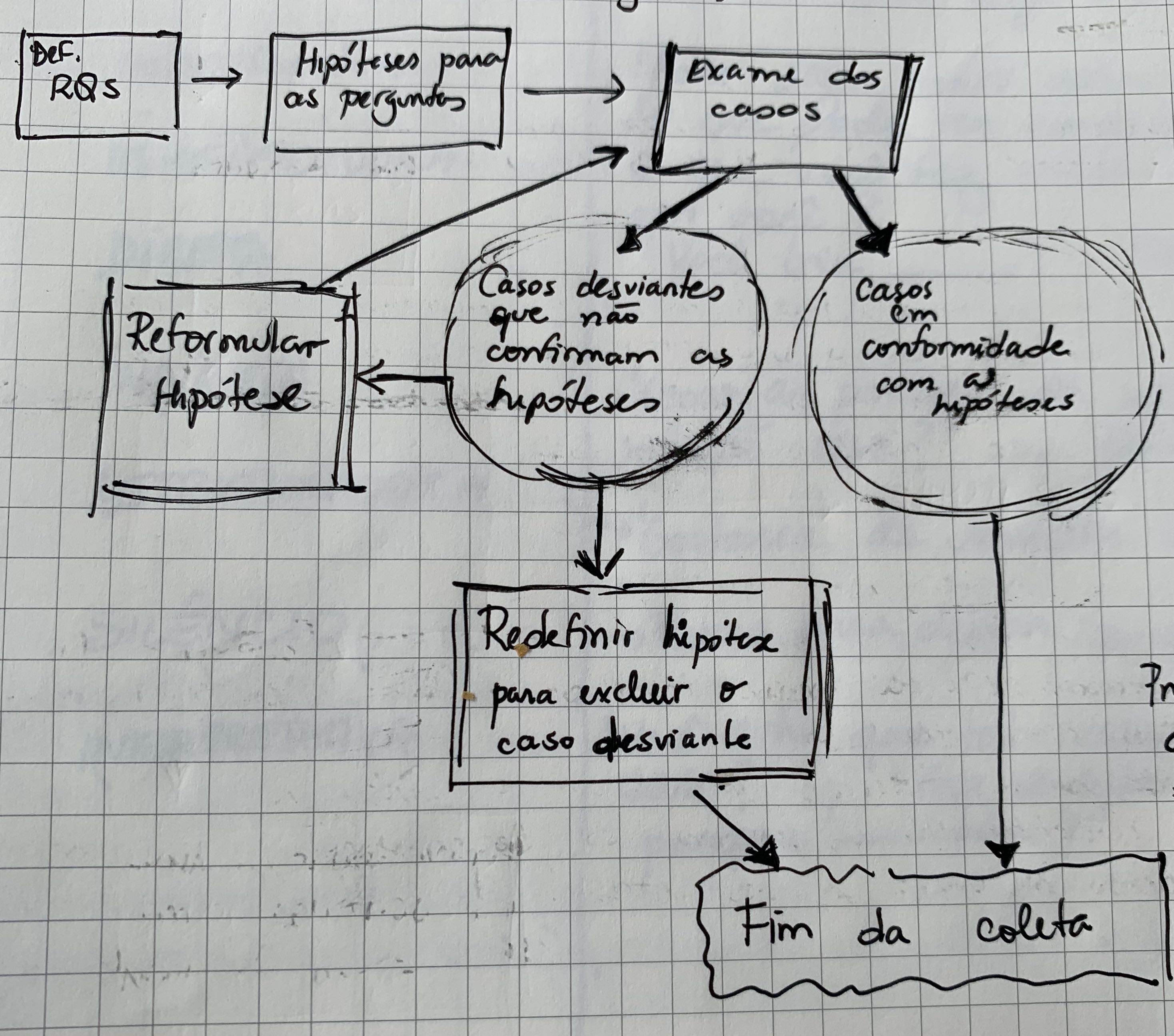

Analytical induction

Approach from the past (40s,50s)

Thematic Analysis

The aim is to identify, analyze, and report themes within data. Themes are patterns of meaning that capture something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represent some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.

Researchers identify themes through a process of coding and organizing the data, but the process is not as iterative or focused on theory development. Various approaches to thematic analysis exist (e.g., semantic, latent).

As outcome, a rich description of the key themes present in the data, often accompanied by illustrative quotes. It may identify relationships between themes but doesn’t necessarily produce a formal theory.

Content Analysis

The focus is primarily quantitative. It aims to objectively and systematically quantify the content of communication, often focusing on manifest content (what is explicitly stated). It can analyze textual, visual, or auditory data.

Involves developing a coding scheme or framework before data analysis begins. This framework defines specific categories or codes that are used to count the frequency of occurrences of words, phrases, images, or other units of meaning.

The outcome is Numerical data representing the frequency and distribution of coded content. This allows for statistical analysis and comparisons between different groups or time periods. May also include some qualitative interpretation of the findings.

Example: Analyzing news articles to determine the frequency of positive and negative portrayals of a particular political candidate. Counting the number of times specific words related to climate change appear in corporate sustainability reports.

Grounded Theory

Most used framework (origin: Glaser and Strauss 1967); hard to define today, there are several approaches. Sometimes GT is only used because the theory is strongly linked to data (when it is only an inductive approach). Often, researchers use one or two features.

Good about GT: You can learn about gaps and holes in the data, right at the preliminary phases of the research

Criticism about GT:

- It is not acceptable there is such thing as a neutral observer, in relation to a given theory.

- It is doubtful to say that GT can generate a formal theory

- The difference between concept and category is vague, to say the least

- Too much fragmentation of data; narrative unity is lost

Objectivist GT: the approach professed by Glaser, Strauss, Corbin, studying a reality that is external to the social actors

Construtivist GT: (Charmaz 2000) - Assumes people create and maintain significant worlds through dialectical processes, which provide meaning for realities and action. Categories and concepts emerge from the interaction of the researcher with her action field and data.

Techniques & Tools for Grounded Theory

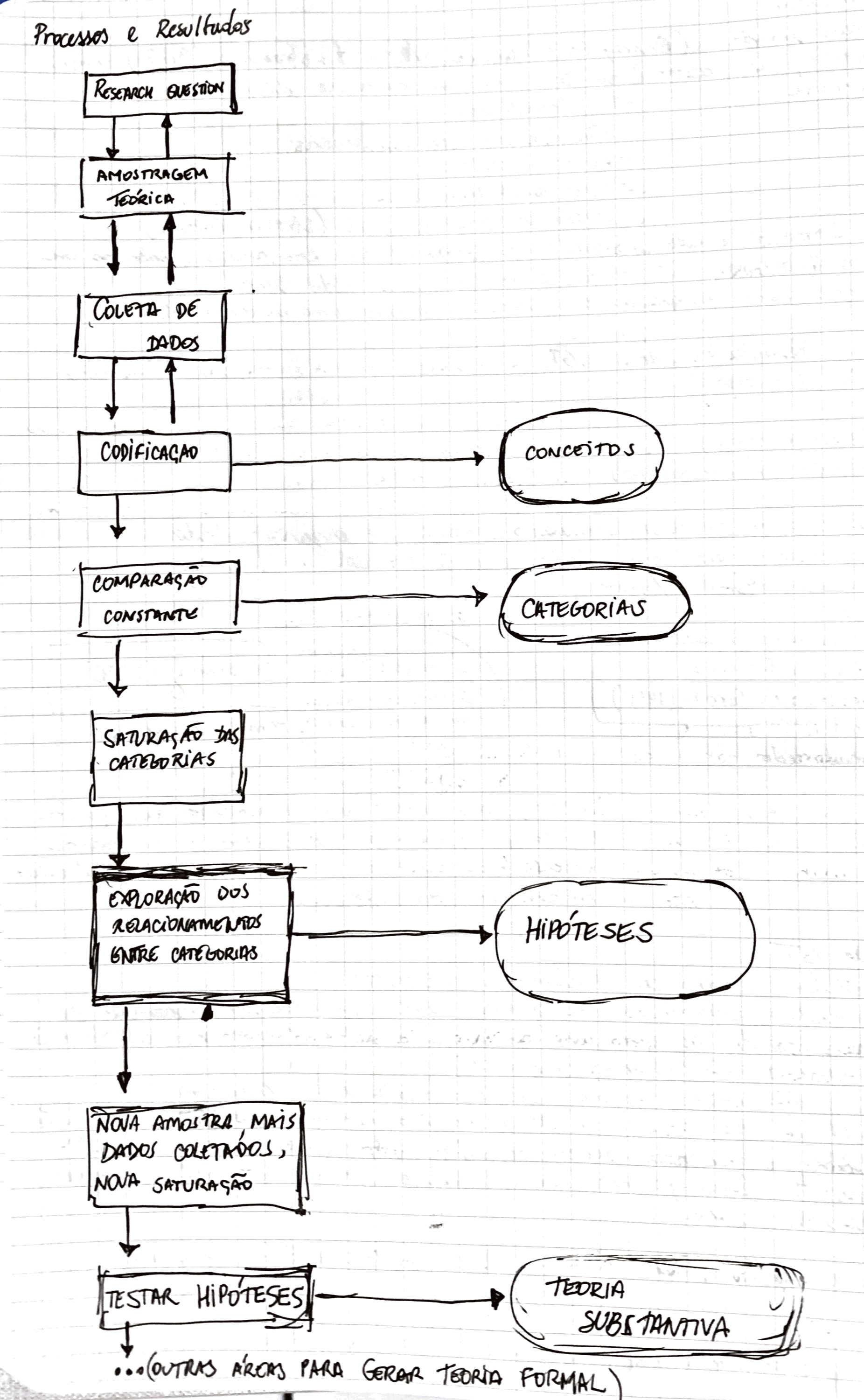

Theoretical Sampling

Process of data collection: analyst collects, codes and analyzes data, and decide which data is gonna be collected next, and where, in order to further develop the emerging categories.

It is a continuous process, rather than a single step (as in probabilistic sampling, which is inadequate to qualitative analysis).

Emphasizes theoretical saturation as the criterion to decide when to stop collecting data, over a particular theory or category set.

Theoretical saturation is when a number of interviews/observations establish the basis for a category, supporting its relevance.

In this case, there is no point in going on with data collection for a given set of categories. Rather, one should try to come up with hypotheses over new emerging categories, concentrating efforts to collect data about them.

Coding

Labels, separate, compile and organize data.

Types of coding:

Open, axial, selective (Strauss and Corbin 90)…not always useful, hard to tell one from another; also, may suggest early end of theory conception.

More useful: initial and focused coding (Charmaz 06)

Initial coding: line-by-line coding

Focused coding: emphasizes most common codes, review and join them in categories.

Initial coding

Examples of initial coding (starts with a verb): ‘receiving news from other people’, ‘being left out’, ‘facing identity issues’, ‘experiencing increasing pain’,’not able to take pain’

“Coding establishes the bones of analysis, the theoretical integration form the functional skeleton”

Questions to develop initial codes (avoid preexistent theories/concepts)

- Which general category does this data item fit?

- What does this item represent?

- What is this item about?

- Which topic is this item fit?

- What is the question about the topic that is made in this item?

- Does this item imply any answer in the topic?

- What is happening here?

- What are these people doing here?

- What are the people saying they’re doing?

- What do these data suggest? Under which point of view?

Benefits of a good code: Remains open; close to the data; simple and precise; short; preserves the action; compare to other codes.

Guidelines:

- Break data into their component parts or properties.

- Define the actions over which data is founded.

- Look for tacit assumptions

- Explain implicit actions and meanings

- Cristalize the importance of points of view

- Compare data

- Identify gaps in data

Questions that help to see actions and significant processes:

- What are the processes in action here? How can I define them?

- How does this process develop?

- How do participants act when they get involved in the process?

- What does the participant think or feel when she’s involved in the process? What does her behavior indicate?

- When, why and how does the process change?

- What are the consequences of the process?

In vivo codes: use participants’ own terms to name the code; help develop implicit meanings

Focused Coding

Use the most frequent/significant previous codes to analyze data more generally. Codes condense data and improve comparison and manipulation.

Transforming data into hypotheses/theories: Define how to substantive codes may relate with one another, to conceive hypothesis to build up theories.

Guide: Glaser 78 define 18 theoretical coding families - six Cs: Causes, Context, Contingencies, Consequences, Covariances, Conditions (in 98, he extends them with more families).

Memo Writing

Intermediate steps between data collection and paper writing

Helps establish relationships among concepts.

Informal in style, made to the researcher’s own reading. Can be refined later.

What to do in a memo:

- Describe how a category has emerged or changed

- Identify beliefs/assumptions to support the category

- Insert categories within arguments

- Define a category’s properties

- Details processes

- Offers empirical evidence for categories

- Has a significant title

- Offer conjectures

- Identify gaps to be checked

- Ask questions about a category

- May include diagrams

Benefits of memos:

- Make you stop and think about data

- Treat codes as categories for analysis

- Develop the researcher’s writing voice and rhythm

- Throw ideas to check in future collection

- Avoid preconceptions on data

- Demonstrate relationships among categories

- Find out gaps

- Assure confidence on the analysis

- Links collection with analysis and reporting

Constant Comparison

Data is compared with data to find similarities and differences (within an interview or among interviews).

Compare data from the same interviewee in two different moments

Compare observations about events in distinct times and places

Compare routine tasks and their differences in time

Outcomes

Concepts and Categories

They are hardly distinct. While concepts could be just labels to discrete phenomena, categories are concepts elaborated to the extent they represent a real-world phenomenon, that groups one or more concepts. Categories contain properties.

Hypotheses

Initial impressions about the relationship between the concepts/categories.

Theory

Set of well-defined categories, systematically organized, through relationship sentences, to build up a theoretical framework that explains some relevant social phenomenon.

Substantive theory: build to a specific empirical area (the most common)

Formal theory: Comprehensive to several substantive areas.