Threats to Validity

A researcher must, somehow, guarantee the quality of her research. Validity is the term we use to discuss the quality of a proposition, inference, or theory. It must be stressed that we don’t judge whether a given research is valid or some measurement is valid; we only judge whether the research results are valid. We end up considering the quality of the results by the applied methods. Still, it needs to make more sense to say if a method is valid.

Campbell (1979) describes validity as the best available approximation for the truth or falsity of propositions, including cause-effect relationships.

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Considering the steps of a research study, each one demands a certain kind of validity. For instance, a correct measurement guarantees the construct validity of the conclusions.

-

External validity concerns sampling

-

Construct validity concerns measurement

-

Internal validity concerns study design

-

Conclusion validity concerns result analysis

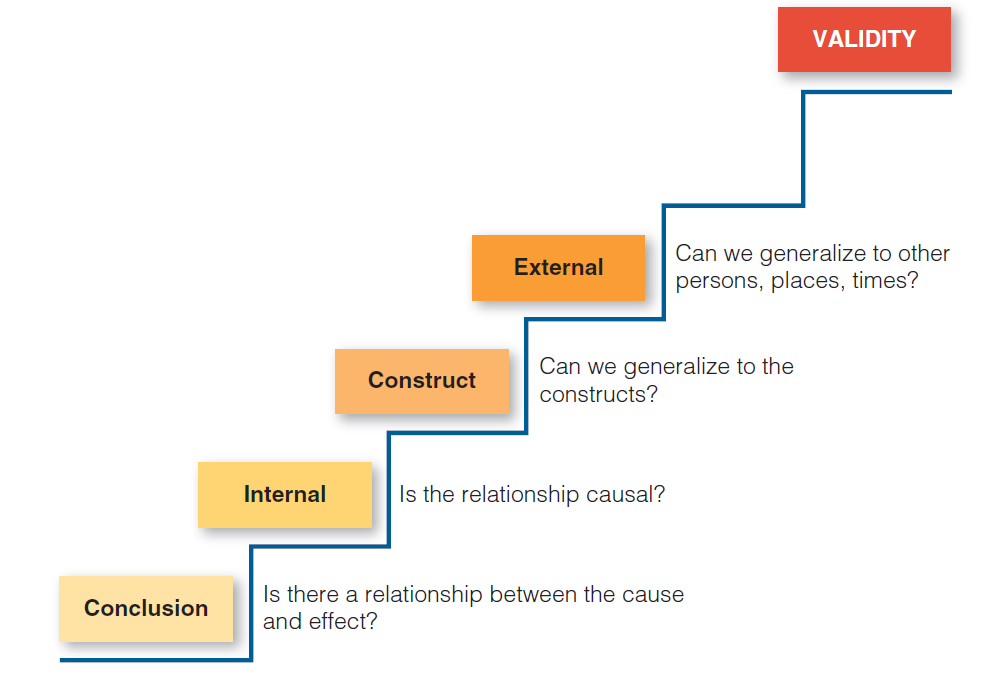

From here on, we can adopt a specific order for dealing with those validity types. The other types are built from conclusion validity, using a bottom-up process. Adopting this order when writing them in the paper helps a lot. See the figure below for reference.

-

Conclusion validity. Is there any relationship between the study variables? Several conclusions are demanded by questions like this. Look at the validity of each conclusion, evaluating the analysis methods and tools to see how the study addresses the type of validity. In the old days, it was called “statistical” conclusion validity. Example: if we’re doing a study examining the relationship between experience level and productivity, we eventually want to reach some conclusion. Based on our data, there is a positive relationship that more experienced developers tend to present higher productivity. In contrast, those with less experience tend to be less productive. Conclusion validity is the degree to which our conclusion is credible or believable. Although conclusion validity was initially thought to be a statistical inference issue, it has become more apparent that it is also relevant in qualitative research. In an observational field study of software leaders, the researcher might, based on field notes, see a pattern that suggests that woman leaders are more likely to be concerned with developer satisfaction. Although this conclusion or inference may be based entirely on impressionistic data, we can ask whether it has conclusion validity, that is, whether it is a reasonable conclusion about a relationship in our observations.

-

Internal validity. Given you found a valid relationship in the previous validity, can we say which type of relationship this is? Is it cause-consequence? Or is it only correlation? The internal validity of a study can be threatened by many factors, including errors in measurement or the selection of participants, and researchers should think about and avoid these errors. Example: you want to test if a particular testing framework improves bug finding in an experiment with students split into control and treatment groups. After analyzing the results, the treatment group found more bugs than the control group. For internal validity, three conditions are required: (i) treatment and response change together, (ii) treatment precedes response, and (iii) there are no confounding or extraneous factors. Your design must minimize the effects of iii. In this case:

-

testing framework and fewer bugs change together;

-

using the testing framework came before the fewer bugs response;

-

the time of the day, developer experience, or environmental conditions could explain the results.

- Construct validity. Assuming you correctly defined the relationship between variables from the two previous validity types, does your test or measure accurately assesses what it’s supposed to? You have to check how the concepts are made concrete in the study. Example: you want to ask how developers feel stress at work; you conceive of several Likert-scale items. To check whether these items measure stress at work, you have to do a few tasks:

-

A pilot study to check feasibility, reliability and validity.

-

Reliability assessment: first, internal consistency across items that measure the same construct (e.g., Crobach’s alpha); second, test-retest, by administering the survey to a sample on two different occasions (when possible).

-

Validity assessment: content validity (consulting experts in the field), construct validity (statistical factor analysis), criterion validity (compare with other existing metrics) and convergent/divergent validity (compare constructs and check if they follow historical trends).

- External validity. Assuming there’s a reliable relationship between the variables, should you generalize the results to other people, places or times? This is related to the quality of a given sample. It would be best if you considered the following factors: (i) a representative sample of the target population, (ii) diverse settings, (iii) realistic tasks and scenarios, and (iv) possible longitudinal studies.